Record labels and recording artists are supposed to work together to make money. But in some instances, bad deals rob the artists of millions of dollars.

The relationship between a recording artist and a record label is supposed to be symbiotic. An artist creates music for the label, the label promotes and sells the music, and they both share the profits. While top-selling artists like Beyonce and Taylor Swift have gained enough industry clout to have very favorable relationships with their labels, most musicians do not enjoy those benefits. There are many examples of musicians who have had big hits and sold millions of records but have received very little payment for their work because of the terms of the contracts that they signed.

In 1993, music superstar Prince changed his stage name to an unpronounceable symbol and famously was referred to as “The Artist Formerly Known as Prince” until he reclaimed the “Prince” name in 2001. At the time, many people did not understand the point of the name change or thought of it as a publicity stunt.

Prince used the strange pseudonym to protest his treatment by his record label, Warner Bros., with whom Prince had disagreements over the release of his music. Prince’s tactic of painting “Slave” on his cheek during performances led to the popularity of calling toxic record label deals “slave contracts” to indicate that these artists are working incredibly hard for little financial benefit.

Whatever the case may be, the history of the record industry is filled with troubling examples of artists who signed unfair deals. These examples include cases that resulted in bankruptcy, organized crime, and even suicide.

8. Little Richard and Chuck Berry

Many of the early rock and roll pioneers like Little Richard and Chuck Berry signed deals with their record labels that perhaps sounded good to them at the time. However, hindsight has proven them to be very poor decisions. To be fair, few artists at that time envisioned that the two-minute songs that they were writing and recording would remain popular for decades.

Little Richard’s 1955 anthem “Tutti Frutti” was a massive hit for Specialty Records, but the profits largely went to Art Rupe, the owner of the label. He paid Richard only $50 for the publishing rights to the song and gave Richard a paltry half-cent for each record sold. Additionally, some sources claim that Rupe added his name as a songwriter to the single under a pseudonym to make even more money off the record.

As for Chuck Berry, the originator of rock guitar had to share songwriting credit to his first hit, “Maybellene“, with two other men: disc jockey Alan Freed and Chess Records creditor Russ Fratto, neither of whom had anything to do with writing the song. However, Berry eventually learned his lesson when it came to the business side of music – at the time of his death in 2017, Berry’s estate was worth a reported $50 million.

7. Tommy James

Many artists have gotten ripped off by their record labels, but few artists have had their lives put in danger by their label. Roulette Records boss Morris Levy was frequently accused of unscrupulous business practices, including withholding royalties from artists and adding his name as a composer to songs he didn’t write, like “California Sun”, to get songwriting royalties. At the end of his life, Levy was convicted for his involvement in organized crime (Levy reportedly had ties to the Genovese crime family).

Those connections had a major impact on the career of rock musician Tommy James, who had recorded big hits in the 1960s like “Hanky Panky“, “I Think We’re Alone Now”, “Mony Mony“, and “Crimson and Clover“. According to James’ 2010 autobiography Me, The Mob, and The Music, not only did Levy withhold substantial royalties from James (estimated as between $30 and $40 million) but that James was also at one time a target for murder by rival crime families to rob Levy of one of his most valuable assets.

6. Billy Joel

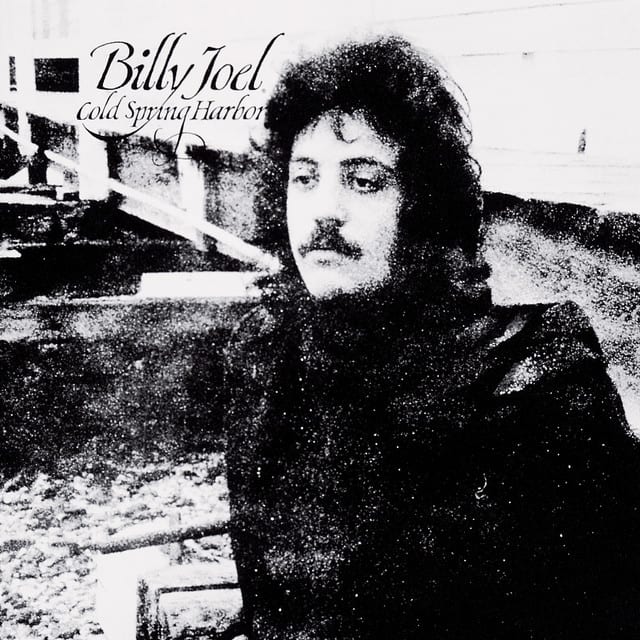

When Billy Joel signed a ten-album recording contract with Family Productions in 1971, he had no idea that he would almost immediately regret the decision and that it would haunt him for almost two decades.

The trouble started with Joel’s first album, Cold Spring Harbor, which was produced by Family Productions head Artie Ripp. Cold Spring Harbor was incorrectly mastered at the wrong speed and gave Joel a much higher voice. Ripp claimed that it would cost too much money to fix and released the album anyway. Joel had signed away ownership of the recordings and publishing of his music, so he had no recourse. The album was a commercial disappointment, and Joel considered it a huge embarrassment.

Joel was able to exit the toxic deal when Columbia Records bought out his Family Records contract in 1972, but Ripp negotiated a four percent cut of the retail price of Joel’s Columbia albums for the next fifteen years. Even after nearly derailing Joel’s career before it began, Ripp reaped the benefits of Joel’s huge success with Columbia in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1978, Columbia head Walter Yetnikoff purchased Joel’s publishing from Ripp and gave it to Joel as a birthday present. But the story didn’t end there. Ripp released a “remixed” version of Cold Spring Harbor in 1983 that finally corrected the album’s pitch to further capitalize on Joel’s superstar popularity.

5. John Mellencamp

Indiana singer-songwriter John Mellencamp’s manager Tony Defries (who helped turn David Bowie into a superstar) forced Mellencamp to perform under the stage name “Johnny Cougar” (and later “John Cougar”) because Defries felt Mellencamp’s actual last name wasn’t marketable.

Mellencamp’s first album, Chestnut Street Incident, was released by MCA in 1976 but was a commercial failure. Though Mellencamp recorded a follow-up album, “The Kid Inside,” MCA dropped him from the label and Mellencamp ended his business relationship with Defries.

Cougar signed a deal with Riva Records, which continued to require him to use his “John Cougar” stage name. In 1982, he had a #1 hit with “Jack and Diane” and a #2 hit with “Hurts So Good” on his American Fool album, and the music videos became staples on MTV. Suddenly, The Kid Inside record from 1978 that DeFries refused to release started to look a lot more valuable to him, and he released it in 1983 to cash in on Cougar’s newfound popularity.

Because of Cougar’s success throughout the 1980s, Riva allowed him to add his actual last name to his stage name. He performed as John Cougar Mellencamp. In 1991, his then-current label, Mercury Records, finally allowed him to drop “Cougar” from his stage name. He has been performing as just plain-old John Mellencamp ever since.

4. Toni Braxton

Despite selling nearly 70 million records worldwide, singer Toni Braxton has filed for bankruptcy twice. While Braxton’s spending habits were heavily criticized after her first bankruptcy filing in 1997, her legal team revealed that Braxton was only earning 33 cents per album sold and her label, Arista Records, had refused to raise that rate in two contract negotiations. Braxton was also being charged by the label for promotional expenses, which reduced her royalty payments to negligible amounts. Braxton claimed that she only received a single royalty check for $1,972.

A contract renegotiation with Arista helped Braxton out of the first bankruptcy. But the story didn’t end there. In late 2002, Braxton asked Arista to postpone the release of her More Than a Woman album because she was pregnant and did not believe that she would be able to properly promote the record because she was required to remain on bed rest. Arista refused to delay the release, which required Braxton to promote the album in a limited capacity. More Than a Woman was a commercial disappointment, and Braxton and Arista parted ways the following year.

In 2008, Braxton again filed for bankruptcy after health issues caused her to abruptly cancel her Las Vegas residency.

3. Badfinger

The rock group Badfinger was off to a promising start when they signed a record deal with Apple Records, the music label founded by the Beatles, in 1968. However, the band signed a disastrous management contract with American businessman Stan Polley in which he received all of the band’s money and paid them on salary. In addition to Polley’s mismanagement of Badfinger’s finances, he had signed the band to a new contract with Warner Bros. in 1972 after Apple had financial troubles of its own.

The Warner Bros. contract stipulated that Badfinger had to release a new album every six months for three years – a grueling commitment. Despite having four hit singles before signing, the band members netted very little advance money from the contract. Worse off, Warner Bros. quickly became suspicious of Polley’s financial management, and the band became engrossed with legal issues.

Warner Bros. grew disillusioned by the entire situation and put very little effort into promoting the band. Badfinger only recorded two albums for Warner Bros., and the second album, 1975’s Wish You Were Here, was withdrawn after less than a year because of these issues. Warner Bros. rejected the third album Badfinger recorded for the label, Head First, and it was not released until 2000.

Frustrated by the legal entanglements and learning that much of the money the band earned had been “lost” by Polley, guitarist Pete Ham committed suicide on April 24, 1975. The financial issues continued, and in November 1983, bassist Tom Evans also committed suicide shortly after an argument with bandmate Joey Molland over the band’s business matters. It was not until 2013 that the band’s various financial issues were resolved.

2. Tyga

Over the last three decades, rap and hip hop labels have been notorious for signing artists to recording contracts that include terms that are not beneficial to the artist. One of the most high-profile contract disputes in recent years occurred between rapper Tyga and his label Cash Money Records.

When only 18 years old, rapper Tyga signed with Cash Money. Tyga later revealed that his lawyer was also representing Cash Money at the time he signed the deal. Unsurprisingly, the contract was extremely favorable to the label, and in 2017 Tyga said that he never received any royalty payments of at least $12 million that he estimated that the label owed him. After Tyga filed a $10 million lawsuit against Cash Money over the royalty issue, label head Birdman claimed that Tyga owed the label money because of the advances that the label paid him.

In 2019, Tyga dropped the lawsuit, with speculation that per the terms of his original contract he never earned royalties for any of the music he recorded for Cash Money.

1. Jackson 5

The Jackson 5 sold a massive number of records for Motown in the early 1970s, and the family band worked tirelessly to put out new music – the Jackson 5 released three albums in 1970 alone. Unfortunately for the band, they only earned 2.8% royalties on their record sales and had no creative control over the music the band was recording. Because the Jackson 5’s songs were largely written by Motown’s in-house team The Corporation or were covers of songs from the Motown catalog, the group was not earning money from songwriting.

When the Jackson 5’s contract ended in 1976, the group signed a deal with Epic Records with a royalty rate that was nearly ten times higher than the rate in their Motown contract. However, the band had to change their name to the “Jacksons” because among many other things, Motown owned the rights to the name “Jackson 5.” While the Jacksons continued to have several hits as Epic Records artists, none matched the popularity of their Motown hits.

Conclusion

Many pop musicians sign contracts when they are very young and have a limited understanding of the entertainment business. Often they are just overwhelmingly excited to have a record deal offered to them that they take very little time to review the contract that they are signing. They may even be distracted by a large advance or promises of fame and fortune to care about the extremely important details. On the other hand, record labels have used accounting practices (both legal and illegal) to rob artists out of royalties that they would otherwise be owed.